“The Bible says the Lord can fit the universe in the span of His hand.”

Preacher man rocks forward on his heels and wipes his mouth with a blue handkerchief. The organist, who punctuates every idea with a Taa-daa, does her usual, this time with eyes closed and a nodding of the head. I see you ahead. Sandy hair, shaggy, cut by your Daddy’s rusty clippers. Ripped jeans out of necessity, not fashion. We are both five years old in the creaky red building leaning on brick stilts, muggy. Your teeth haven’t grown back yet from the baby-bottle-rot Medicaid pulling. Mine get brushed twice a day.

At fourteen, you father a child with the girl at the alternative school. She is twelve. You have been to the juvenile detention center three times. Your parents want to rear that baby, too, but even at this age, you know better. You sign him up for adoption. I hear you cried, rare for you. It is my aunt, your cousin, who says so. She is filing her nails, watching HeeHaw, and she turns to sing along to Loretta Lynn. None of us come to your house. You cuss my mom at nine, and punch me in the face at seven. You are incorrigible. I learn that word at eight. The only one who really tries is my dad. When you were fifteen, he taught you to read.

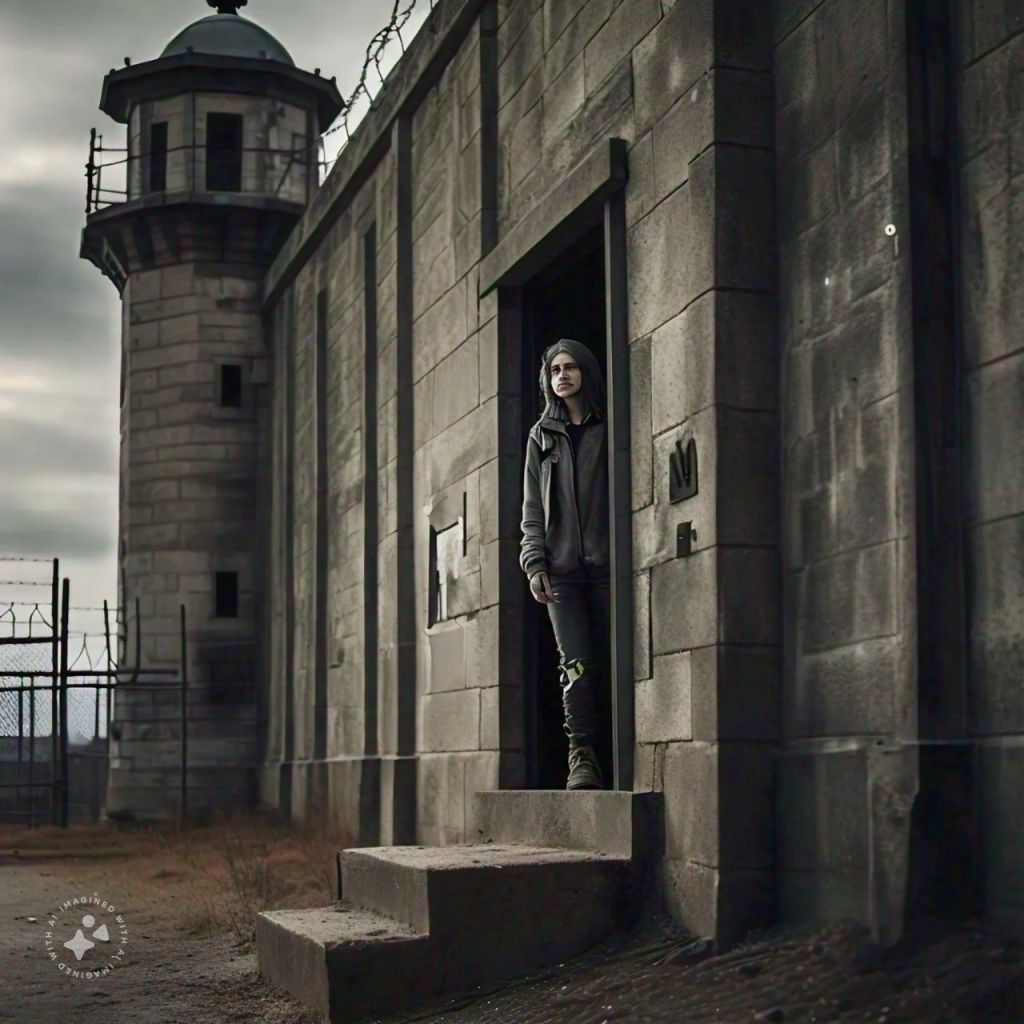

Two years later you are in prison, tried as an adult for making meth in the woods behind a Scamp trailer. Even my father doesn’t visit. “Cannon fodder,” my uncle says. “I said that when he was three and had those rotten teeth.” You come out with more tattoos and a hardening of the eyes. My father lets you cut his grass, and borrow money. You say you will be a welder. You say you will go clean. Then it happens.

You break in, high, and pick up the bat that lies beside my father’s bed. The coroner calls me the next week as I am pressing my nose inside my dad’s grey jacket, hoping to catch his scent. I’m not allowed to see the body. There is no way to tell how many times he’s been hit. You confess later that day. You cry, but only briefly and maybe for yourself. In two years you go back to prison, the worst one in the state. Chained wrist to ankle, wearing blood-colored clothes on a grey bus with deputies bearing sawed-off shotguns. They call it hell’s gates. There you meet Billy DeBeer, who runs the prison ministry.

You start going every Wednesday because the food doesn’t have maggots and they teach you to play guitar. He tells you of David’s men, who fought for him before he was king. The outcasts. Society’s scum turned warriors. “It ain’t over til it’s over,” Billy says, speaking of his own days in solitary confinement. “And you still above ground.” He leans in, widening his eyes. “God’s a big God. He can forgive. Just get on your knees and cry out.”

Your nightmares change to dreams. No longer does my dad lean in to strangle you. No more does your dad beat you with his cane. You see Jesus. He tells you you aren’t forgotten. He tells you these walls, this life sentence, is your mission field. He tells you you can overcome. Just ask for forgiveness. Just believe. You wake up to a guard kicking you with mud colored boots. Can you survive this? The guy in the next cell hangs himself. You used to swig his smuggled gin. You are cut deeper each day. Finally, you have had enough. One night, you get on your knees. You ask God to save you. Forgive you.

Finally, a peace you’ve never known. Finally, some of the rage seeps out. You get baptized in an aluminium tub the next week. At 30, you are reborn to ministry. You share your testimony. “I didn’t want to die like Larry. I can survive. With Jesus, we can do anything.” You are getting good enough to play with the band. You have started praying for your enemies. The couple who adopted your son make contact. It is enough. You got a life sentence, but now you are finally living.

Bio: Mary Eileen Ball lives in the Deep South. She has been published in Agape Review, Clayjar Review, Heart of Flesh, and others. You can find out more at https://www.facebook.com/maryeileenball/.

Discover more from PAROUSIA Magazine

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.